| Resources |

| History ...links to 1916, Lockout, Civil War |

| Language ... |

| Gay ... |

| An Ireland ... |

| At Swim home ... Reviews ... Extracts ... Gallery ... Abroad ... Resources ... |

| Jamie O’Neill home |

| At Swim, Two Boys Kilbrack Disturbance Short Stories Journalism Press! |

| Contact |

This text is taken from Chapter Five, “The Dublin Slums”

ex Shadows: An Album of the Irish People 1841–1914

by Michael O’Connell; The O’Brien Press, Dublin 1985.

The nineteenth century was to be decisive in Dublin's history. In the early 1800s, the city was at the height of its splendour, the home of nobility, and graced by fine buildings and parks. By tragic contrast, at the close of that same century, the capital was in ruins, pitted by derelict sites, its nobility vanished and the remaining population demoralised by unemployment and almost vanquished by poverty.

Such devastation was brought about by greed and immorality, official incompetence and neglect. The first death knell sounded when Grattan's Parliament was dissolved and the Act of Union took place in 1801. No longer would Dublin be the seat of Parliament and the centre of its own universe - it would soon become a neglected backwater. 'Society' moved to London and took with it the wealth which would otherwise have been invested in indigenous industry. Dublin would therefore escape the worst excesses of England's industrial revolution. but the price was enormous.

Without native wealth, industries in Dublin faltered and then died until the only significant ones remaining were brewing, distilling and biscuit-making. Apart from these stalwarts, only unskilled and labouring work was available in the city, much of it in the docks into which were imported almost all the manufactured goods required by the country and from which agricultural produce mainly was exported. For these low-skilled jobs wages were pitifully small, the average being eighteen shillings per week. Class differences in the city were enormous – a Grafton Street shop at the same time was advertising ladies' summer suits at over eight times those eighteen shillings.

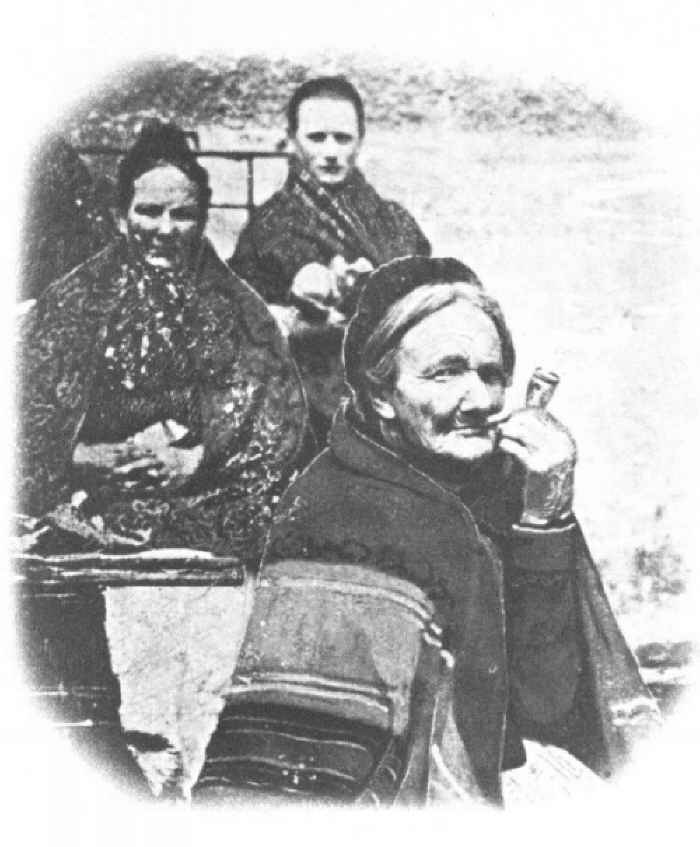

Meanwhile, Dublin was declining against the background of an ailing agricultural sector, with the result that people from country areas began to crowd into the city in search of work. These new migrants were to thrive in their new home. Healthier and sturdier than their wretched city counterparts, they successfully applied for jobs in the police force and in companies such as Guinness's. Similarly, an unseen network of people from 'back home' already established in the city, ensured their entry to trades and the better lifestyle this could buy. Because of their regular income, they could afford higher rents than the unskilled Dubliners, and so could aspire to being housed by Dublin Corporation or the Artisans' Dwelling Company – the hall-mark of the working class. Between 1821 and 1891 the population of Dublin grew by 66,400. When we remember that the city area referred to is that bounded by the two canals, an area of 3807 acres, we have some understanding of the congestion in Dublin: 65.6 people per acre.

One of the first requirements of a growing population is, of course, shelter, and it was here, after the lack of employment opportunities, that Dublin most betrayed her citizens. Tenement houses, as they were called, once the grand Georgian dwellings of the now departed wealthy, became home to Dublin's poor. But whereas a house once had sheltered one family, now they were subdivided and often sheltered as many as five or six families.

| Tenements | occupied by | Families |

| 3270 1778 104 8 1 | 1 – 5 6 – 10 11 – 15 16 – 19 24 |

In summary, Dublin housed almost 26,000 families in tenement houses and 7800 of those in one-roomed rentings.

Such overcrowded conditions had not gone unnoticed and there was no shortage of inquiries into health and living conditions in the tenements. Acts of Parliament to improve the situation abounded, and were passed in 1866, 1867, 1868, 1875, 1879, 1882, 1890 and again in 1908. We can only surmise now that two essential ingredients necessary for their implementation were absent – money and political will. The lack of the latter may have been caused by the fact that when the nobility and gentry departed from Dublin, they were soon followed by the city's new middle classes who left for emerging suburbs such as Dalkey, Rathmines and Pembroke.

Although their businesses were situated in the city, they now paid rates to their new boroughs. Those remaining were elected to Dublin Corporation and their record in improving the city is less than praiseworthy. Indeed, some of the members of the Corporation, Alderman O'Reilly, Corrigan and Crozier, were owners of tenements. Such owners were entitled to tax rebates on rent from tenements if they carried out improvements to their property. It was not unusual, however, for some landlords to obtain waivers from these improvements and still be in receipt of the tax rebate, as happened with Aldermen O'Reilly and Corrigan, who obtained their waivers from Sir Charles Cameron, the then Medical Officer of Health.

Although their businesses were situated in the city, they now paid rates to their new boroughs. Those remaining were elected to Dublin Corporation and their record in improving the city is less than praiseworthy. Indeed, some of the members of the Corporation, Alderman O'Reilly, Corrigan and Crozier, were owners of tenements. Such owners were entitled to tax rebates on rent from tenements if they carried out improvements to their property. It was not unusual, however, for some landlords to obtain waivers from these improvements and still be in receipt of the tax rebate, as happened with Aldermen O'Reilly and Corrigan, who obtained their waivers from Sir Charles Cameron, the then Medical Officer of Health.

The inevitable happened in September 1913 in Church Street when two tenements collapsed. Had all forty people who lived there been at home it would have been a major tragedy, but, nevertheless, seven were killed. Considering the age of the tenements and the fact that their walls were filled with timber which had rotted, bulged and weakened the walls, it is amazing that more such tragedies did not occur. The response to the deaths in Church Street was swift, and a public sworn inquiry was appointed by the Local Government Board for Ireland to 'inquire into the Housing Conditions of the Working Classes in the City of Dublin'.

The committee reported in 1914, and having heard from seventy-six witnesses and visited the tenements, their outrage at their discoveries can be seen breaking through their parliamentary and measured language. Among the first of the ills of the tenements to be listed was invariably the dirt. The hall and stairways used in common by perhaps six families were described as 'exceedingly foul', and the filth of the backyard and front area so polluted as to 'beggar description'. The committee found human excrement scattered about the yards of the tenements in nearly every tenement visited and in many cases even in the passages of the houses. The toilets, shared as they were by thirty or more people, were putrid. All water for cooking, cleaning and washing had to be carried in buckets, often up eight flights of stairs.

Cleanliness, then, for individual families demanded almost superhuman effort. The committee found it gratifying to report that in many instances efforts had been made by families to keep their rooms tidy and clean.

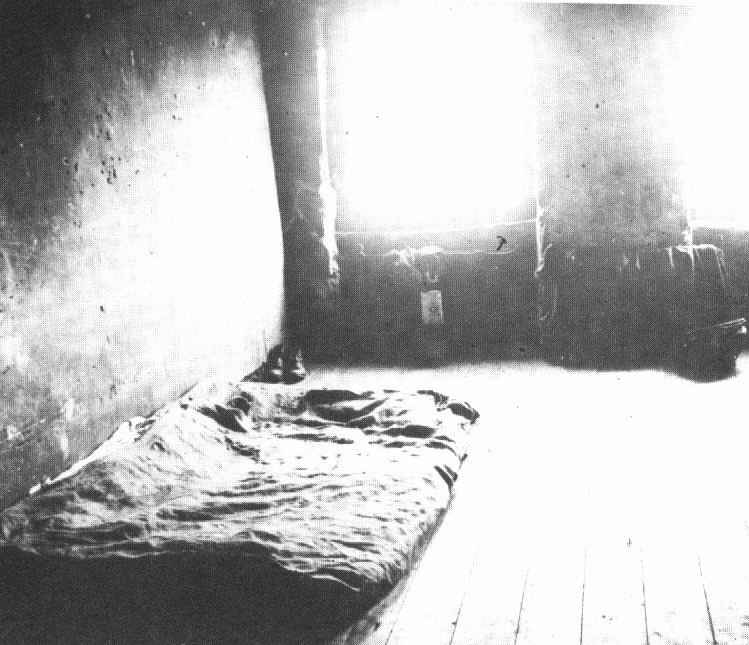

Furniture for these rooms was scarce and might consist only of tables and chairs; in bad times – during sickness or unemployment – these were quickly dispensed with and replaced by boxes. The one or two beds in which all the family slept would also be sold or pawned and in their place would appear a 'repellent assortment of rags' as the family's resting place. Ovens and stoves were almost unknown in Dublin's tenements and all cooking was done on the open fire. But, in fact, little cooking was done anyway as the meagre budget often bought only bread and tea for two of the day's meals. Even in worst times efforts would be made to provide a good dinner for the family breadwinner, as without his health and strength life would be even worse. Vegetables other than potatoes, cabbage and onions were rarely cooked and to these might be added cheap American bacon or herrings to complete the dinner. Fruit, desserts, cakes and sweets were almost never seen and the diet was wearying in its monotony.

Furniture for these rooms was scarce and might consist only of tables and chairs; in bad times – during sickness or unemployment – these were quickly dispensed with and replaced by boxes. The one or two beds in which all the family slept would also be sold or pawned and in their place would appear a 'repellent assortment of rags' as the family's resting place. Ovens and stoves were almost unknown in Dublin's tenements and all cooking was done on the open fire. But, in fact, little cooking was done anyway as the meagre budget often bought only bread and tea for two of the day's meals. Even in worst times efforts would be made to provide a good dinner for the family breadwinner, as without his health and strength life would be even worse. Vegetables other than potatoes, cabbage and onions were rarely cooked and to these might be added cheap American bacon or herrings to complete the dinner. Fruit, desserts, cakes and sweets were almost never seen and the diet was wearying in its monotony.

Poor diet combined with squalid living conditions were a recipe for a variety of ailments which were to plague Dublin's poor. Tuberculosis was to the forefront of these and decimated families for almost another generation before being finally eradicated. Forty years previously, the physician-in-charge at Cork Street Fever Hospital had attempted to show the connection between bad sanitation and a high incidence of fever – typhus, enteritis, etc. These houses he termed 'fever nests' and described a typical one, in Bridgefoot Street, as follows:

'This house is entered from the street by a passage, with a black and rotten floor, in which are open chinks communicating with the cellar below; the boards are damp, and sodden with dirt; going upwards we find things somewhat better, but the whole upper part of the house is dilapidated; going downwards, we first come to the entrance of a small back yard, a place covered ankle-deep with human filth, a privy and ash-pit totally unapproachable without passing through a sea of dirt, a water-tap running, and washing such of the dirt as is within reach into a pipe sewer which runs through the cellar of the house, and which had a hole through which the sewage passed into the cellar, converting it into a cesspool; this cellar was immediately beneath two rooms inhabited by a family of fifteen, every one of whom has enteric fever. In the same street I find another house with all these characteristics repeated, except the broken sewer. But this house had no sewer at all.' Thomas W Grimshaw MD, Remarks on the prevalence and distribution of fever in Dublin, 1872.

Typhus had still not been eradicated by the early twentieth century and caused thirteen deaths in the years 1902 to 1911. Its place as a major killer disease had been overtaken however by tuberculosis, which in the same period killed 1444 of Dublin's citizens. Other diseases of poverty and overcrowding, such as pneumonia and enteritis, claimed 4600 lives. By contrast rickets, scabies and lice. although a scourge in themselves, were mere inconveniences.

A brief oblivion from squalor, monotony and hardship was devoutly sought and few resisted the lures of the local public house where for the price of a bottle of stout you would also get heat, light, comfort and companionship. And if too much money was spent there, the one and only suit could be pawned on Monday morning and redeemed again the following Saturday in time for Sunday Mass.

When the departmental committee finally reported to Parliament. they recommended the acquisition of derelict sites and the building of new houses for the working classes. Feeling that this ought to be the responsibility of Dublin Corporation, the committee rejected the suggestion that a separate housing authority be established. In a separate rider to the report one of the committee's members, J.F. McCabe, insisted that no piecemeal building programme be undertaken until an entire plan for the city's development was drafted. He was convinced that 'To build without a Town Plan in the old City will prevent effectually Dublin ever becoming what it should be – as beautiful as it own surroundings.'

Meanwhile, Dublin's downtrodden waited, unemployed, ailing and poor in a huddled, and far from beautiful city.

top