| Resources |

| History ...links to 1916, Lockout, Civil War |

| Language ... |

| Gay ... |

| An Ireland ... |

| At Swim home ... Reviews ... Extracts ... Gallery ... Abroad ... Resources ... |

| Jamie O’Neill home |

| At Swim, Two Boys Kilbrack Disturbance Short Stories Journalism Press! |

| Contact |

Chapter 17, The Life and Times of James Connolly

by C. Desmond Greaves. International Publishers, New York, 1971

On Friday August 29 Connolly received a telegram. Industrial war had broken out in Dublin. Larkin had been arrested and charged with seditious libel and conspiracy, together with O'Brien, Lawlor and P. T. Daly. Connolly left at once for Dublin where he found the defendants out on bail and holding a protest meeting in Beresford Place. One of the greatest labour struggles in West European history had begun. For Ireland, indeed, it was a climacteric as fateful as 1916.

In inception it resembled one of those chess openings when pawns fling themselves into the centre of the board only to freeze into minatory deadlock, behind which the real forces manoeuvre for position. The employers had political reasons for trying conclusions with Larkin. Not only had he stirred up those who carried the whole of Dublin society on their backs. His organisation had infused a new spirit into both Trades Council and T.U.C., and the political outcome was a Labour Party. They were expecting Home Rule, and whether it was to be "Rome rule" or not, they intended to be the beneficiaries. He had disturbed their dream of an Ireland safely insulated from the "profane class struggle of the sinful world". Self-government was being conferred only to be snatched away on the one hand by Carson, on the other by the resurgent mob. The dream became a nightmare. How could they defend Home Rule with Larkin on their flank? How could they, on the other hand, defend it without him?

The Dublin employers had founded an Association in 1911 in hopes of "meeting combination with combination". Little headway was made with it, for Larkin held the initiative. His organising activity seemed tireless and endless. Each week he produced ninety thousand copies of the Irish Worker. Raucous, sensational, even hysterical at times, it was a stentorian voice of the people. The smaller employers shivered in the blast, fearing while they hated, until big capital was ready to do battle.

From April to August 1913 Dublin was talking conciliation. The Chamber of Commerce met representatives of the Trades Council under the chairmanship of the Lord Mayor. Both Larkin and Connolly afterwards accused the employers of talking peace the better to prepare war. But O'Brien and the Trades Council took them seriously. So did The Irish Times. According to his apologist, Wright, it was in April that William Martin Murphy decided to slay the blatant beast. His heart bled for Jacobs and the shipping companies who were struggling in the "tentacles" of Liberty Hall. He had ample resources and knew how to bide his time. Conciliation was a useful smokescreen, but there was always the danger that it might be successful.

Tramway boss, newspaper proprietor, owner and investor from Ramsgate to Buenos Aires, he decided to provoke a struggle before the conciliation scheme came to be accepted as a practical possibility. That the A.O.H. [Ancient Order of Hibernians] helped to shape his course cannot be doubted. Throughout the summer there was talk of a compromise between Redmond and Carson, involving partition, devolution, or "Home Rule within Home Rule". The bourgeoisie looked apprehensively around and wondered what would happen if the working class took up the national flag when they dropped it. "The A.O.H. felt itself endangered by Larkinism," wrote Hilaire Belloc's New Witness, adding after the arrests: "Larkin was prosecuted at the instance of a Nationalist politician,^ namely, Devlin. The political motivation of the lock-out which followed has received little attention, but helps to explain the extraordinary implacability of the employers. After Home Rule, whose rule? The future of their class was at stake.

Martin Murphy has been described as a "good employer". His tramwaymen did not think so. Nor did the public; he charged twice the fares for a service inferior to that of Belfast. The description "good employer" dates from the Trades Council's sycophantic days, when any large employer was good. It is surprising that writers with Labour sympathies should have used Wright's Disturbed Dublin as a serious source book. In August 1913, said Larkin, "dog or devil, thief or saint" was being invited to work for the Tramway Company. Hostilities commenced on Friday August 15, when Murphy called together the employees in the despatch department of the Independent [nationalist newspaper] and offered them the choice of the union or the job. The following Monday, as they were leaving work, forty of them were paid off. The city newsboys thereupon refused to sell the Independent and Evening Herald. Motorcars and vans were pressed into service and were followed down Middle Abbey Street by hostile crowds. A young clerk, Martin Nolan, clinging to the reins in the face of lashes from the driver's whip, was overpowered by four policemen and arrested for "obstruction and intimidation". The men of Suttons, the carriers, then stopped work.

On Tuesday the dispute spread to Eason, wholesale and retail newsagent. Their men refused to handle the Independent. Murphy's next act of provocation was on Thursday, when he announced that he "expected demands" on the Tramway Company. His directors decided to suspend the parcels service, and the men were paid off. The political aspect of the struggle emerged more strongly next day. Special Constables were sworn in. But Larkin was a tactician. There were no flamboyant threats. Union officials were seen making contact with the tramwaymen without giving a clue as to what was afoot. Once more Murphy struck. He issued a circular which was sent to every employee by post. It demanded a pledge to continue to work in the event of the union calling a strike. The tramwaymen then held a meeting in the small hours of Sunday morning. Larkin was empowered to call a lightning strike at his discretion.

This was Horse Show week, the height of the Dublin "Season". The Irish Times regarded a strike at such a period as unthinkable. But Murphy declared grimly that he had four men for every potential striker and could moreover supply other employers with all the scabs they wanted. He was determined on a trial of strength. The union had no option.

Work stopped on Tuesday at 10 a.m. Tramwaymen informed their passengers that they were going no further. Leaving their trams standing, drivers and conductors got off and walked home. On that day Murphy visited Dublin Castle, He was assured that the state forces were at his disposal. A marquee was erected at Dun Laoghaire to receive police from Co. Cork. Meanwhile there were clashes between strikers and the few employees still working on the trams. On Wednesday August 27 it was announced that the "skeleton service" would be discontinued at dark.

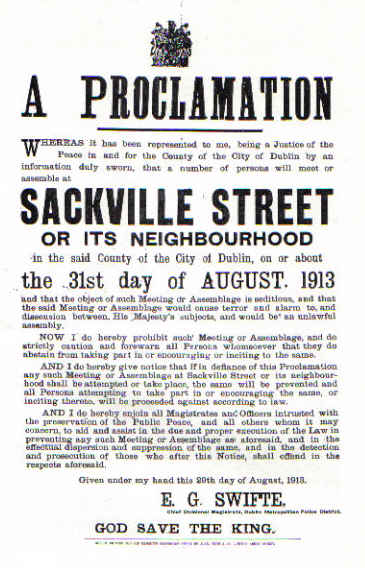

Each night Larkin held a giant meeting by the Custom House. On Wednesday he announced a demonstration in O'Connell Street for the following Sunday. The police provoked some disorder and next day the press demanded the proclamation of Sunday's meeting. Larkin replied defiantly he would hold his meeting proclamation or no proclamation. If the police insisted on fighting, the workers would arm themselves. It was for this speech that Larkin was arrested.

"Now arrest Carson," retorted the Daily Herald. The London Trades Council and British Socialist Party sent indignant protests to Chief Secretary Birrell. The Dublin Trades Council demanded the immediate release of Larkin, and issued an appeal for funds. He was allowed £200 bail, and it was then that Connolly joined him at the meeting in Beresford Place.

The expected proclamation had by then been issued. Larkin held the document aloft before the crowd, and at the conclusion of a fiery speech struck a match and burned it before the crowd. He declared he would hold the demonstration "dead or alive", and then made himself scarce.

Connolly continued in the same vein. He noted the banned meeting was one to be held in "Sackville Street" [the "Ascendancy" name of O'Connell Street], but he thought people might take a stroll through O'Connell Street if only to see if a meeting was being held there or not. He denied the right of His Majesty the King of England to prevent Irish people from gathering in their principal thoroughfare.

Friday's meeting was also broken up by police, but Connolly and Partridge were not arrested till early on Saturday afternoon. Mr. Justice Swifte sat specially to hear the case. It is not true, though it has been stated, that Connolly refused to recognise the court. He utilised the legal machinery that was available, while explaining what he thought of it.

"One point in the indictment," he said, "is that I do not recognise the Proclamation. I do not, because I do not recognise English Government in Ireland at all. I do not even recognise the King except when I am compelled to do so." Regarding the O'Connell Street meeting, he had advised people not to "hold a meeting" but to "be there". At the same time he claimed that "the only manner in which progress can be made is by guaranteeing the right of the people to assemble and voice their grievances". He refused to give bail to be of good behaviour and was sentenced to three months' imprisonment.

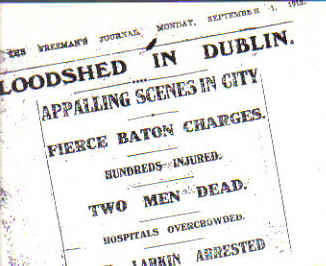

Once the leaders were out of the way, police violence began in earnest. A football crowd at Ringsend showed its resentment against scabs playing in one of the teams. Police quelled their protest with batons. Later in the evening there were clashes between strikers and "loyal" tramwaymen in Pearse Street (then Gt. Brunswick Street). Wild baton charges followed both there and around Liberty Hall, until after nightfall when a "bright and promising" young worker, James Nolan, was clubbed to death. Another, James Byrne, received serious injuries from the police who were copiously supplied with drink. Employers and authorities had the scent of victory in their nostrils.

As the terror mounted, William O'Brien did what he considered the sensible thing. Larkin was missing. Connolly was in jail. He transferred Sunday's demonstration to the I.T.W.U. recreation ground at Croydon Park, "in the interests of peace". This action was speedily repudiated by Larkin, who had made his own plans. It is the

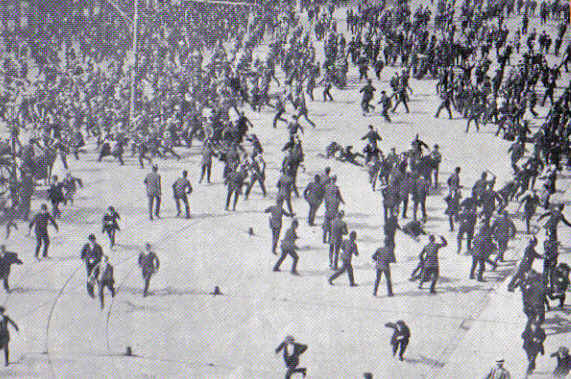

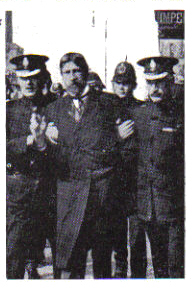

explanation of the fact that so few strikers were in O'Connell Street when Larkin drove up to the door of the Imperial Hotel wearing a false beard and Count Markiewicz's frock coat. He was bowed into the foyer and made his way, still bent almost double, to the balcony, where straightening himself, he announced that he had kept his promise. He was soon arrested and led away. But the effect was electrical. This spectacular defiance of authority seemed symbolic of the workers' invincibility. The cry went up "It's Larkin", and then followed the historic baton charge which gripped the imagination of Europe and completely identified the political and industrial aspects of the conflict. The police laid into the crowd with savage and indiscriminate violence, sparing neither age nor sex. Many of those present were simply passers-by or worshippers returning from Mass in Marlborough Street. That night, and on many nights that followed, the police ran berserk, breaking into workers' homes, shattering delph and furniture, arresting without provocation, clubbing without mercy or compunction. That Sunday there were over four hundred civilians injured against thirty constables. James Byrne died in hospital during the morning.

explanation of the fact that so few strikers were in O'Connell Street when Larkin drove up to the door of the Imperial Hotel wearing a false beard and Count Markiewicz's frock coat. He was bowed into the foyer and made his way, still bent almost double, to the balcony, where straightening himself, he announced that he had kept his promise. He was soon arrested and led away. But the effect was electrical. This spectacular defiance of authority seemed symbolic of the workers' invincibility. The cry went up "It's Larkin", and then followed the historic baton charge which gripped the imagination of Europe and completely identified the political and industrial aspects of the conflict. The police laid into the crowd with savage and indiscriminate violence, sparing neither age nor sex. Many of those present were simply passers-by or worshippers returning from Mass in Marlborough Street. That night, and on many nights that followed, the police ran berserk, breaking into workers' homes, shattering delph and furniture, arresting without provocation, clubbing without mercy or compunction. That Sunday there were over four hundred civilians injured against thirty constables. James Byrne died in hospital during the morning.

But "law and order" had overreached itself. So great was the revulsion of feeling that even the Cork A.O.H. protested against the police terror. At the British T.U.C., then meeting in Manchester, Larkin's arch-enemy, Sexton, moved a resolution demanding freedom of assembly in Dublin.

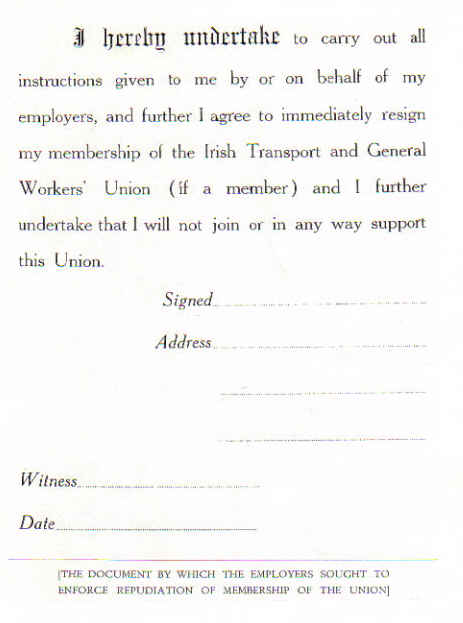

On Monday morning, September I, Larkin was charged once again. This time bail was refused. Now that the workers' leaders seemed likely to remain locked up for some time, the smaller employers took heart. Jacobs and the coal merchants locked out their men that same morning. Two days later four hundred and four employers, including some who had not previously been members of the Association, bound themselves by "solemn vows and still more binding financial pledges" (as Connolly put it) not to employ any worker who refused to sign an undertaking not to become a member of or assist the I.T.W.U. in any way. It was an undertaking so sweeping as to be unique in Labour history, and caused consternation on both sides of the channel.

Larkin was remanded till the following Monday, and events moved with vertiginous speed. Keir Hardie landed in Dublin, visited Connolly in jail and went on to Belfast where he secured the support of the Trades Council. It was on that day that Connolly's cross-channel dockers resigned in protest against his "ungodly speech". A British T.U.C. delegation arrived in Dublin and conferred with the employers in the Shelbourne Hotel, while strikes spread on the North Wall and the master builders gave notice of a lock-out in accordance with the employers' agreement. Twenty thousand people marched in the funeral procession of Nolan, and the police dared not intervene. Nor were they in evidence at Byrne's funeral or the mass meeting in O'Connell Street called by the British labour leaders, whose main preoccupation was to settle the strike before it spread to England. The Dublin employers were unaffected by their sweet reasonableness. The issue was engaged; the deadlock was plain to be seen. One side must give way. The issue of action in England dominated the struggle until December.

Connolly's first action after being sentenced was to send for Danny McDevitt from Belfast. He must collect a small bag from Moran's hotel, pay his bill and take the bag back to Belfast. The bag was unlocked. McDevitt was surprised at this request. Was there nobody in Dublin to be entrusted with such a small thing? Connolly offered no explanation, but McDevitt gathered that he was not anxious that the financial condition of the union in Belfast should be too well known in Dublin, and felt the open bag would prove too much of a temptation to the curious. His other request was for grammars of the Irisn language. These were sent in, but by the time they arrived Connolly had decided that too much was going on outside. Study must wait. On Sunday September 7 he went on hunger strike.

His detention was of doubtful legality. Great indignation was aroused when it leaked out that Mr. Swifte, the magistrate, was a substantial shareholder in the Tramway Company. The authorities tried to keep the hunger strike dark, and no forcible feeding was attempted. But as protests mounted they became alarmed. This mood of the people was completely new. They had rebelled, and heaven had not fallen in on them. A new air of confidence that they had power and could use it affected the entire working class.

Lillie and Ina visited Connolly on the seventh day and found him weak and feverish. A deputation composed of William O'Brien, Sheehy-Skeffington, P.T. Daly and Eamon Martin of the Fianna waited on the Lord Lieutenant. Mrs. Connolly was staying at the Martins' home. In the afternoon the vice-regal car appeared at the door, bearing orders to the Governor of Mountjoy that Connolly should be released. Mrs. Connolly and Ina thereupon returned to Mountjoy with Martin, and took Connolly by taxi to the house of Countess Markiewicz. The preceding Thursday Larkin was allowed bail, though a true bill had been found against him. The higher authorities were beginning to wonder whither events might lead. The weapon of thuggery had to be replaced by another, the weapon of starvation.

Connolly rested at Surrey House, Rathmines, for a few days. Meanwhile the efforts of the British T.U.C. leaders to effect a compromise were bogging down and a sympathetic strike movement began in England. Liverpool dockers came out, and were quickly followed by railwaymen in Birmingham, Yorkshire and South Wales. The Daily Herald, utilising the services of Sheehy-Skeffington and W.P. Ryan, constantly urged support for Dublin. Even there, not all forces were yet engaged. The master builders declared their lockout, and with the completion of the harvest the farmers of Co. Dublin followed suit. The struggle engulfed one section after another. Even the children were drawn in. Pupils of Rutland Street school refused to work with textbooks distributed by Easons, and were evicted from the premises by the police.

Connolly completed his recuperation in Belfast. Before returning he wired Nelly Gordon. He was determined to use his reappearance in order to stimulate solidarity in the north. She brought out the Non-Sectarian Labour Band and a demonstration of dockers and mill-girls awaited him at the G.N.R. station. At the same time Orangemen gathered in Shaftesbury Square singing "Dolly's Brae". From the one came drumrolls and cheers, from the other catcalls and volleys of stones. Despite brickbats and some revolver shots, a meeting was held. Flanagan made a strong attack on religious sectarianism and Nelly Gordon welcomed Connolly back to Belfast. The procession returned to the union office. It was ironical that on that same day when the Orangemen discharged their shots, a section of the clergy in Dublin condemned "socialism" and demanded the formation of a breakaway union. One or two "yellow" sheets were started with employers' money. But the A.O.H. move was unheeded by the strikers.

While Connolly spent his few days in Belfast, the promising sympathetic strike movement across the channel came to an end. J. H. Thomas, instead of standing by the railwaymen who were victimised for supporting Dublin, helped the employers to dismiss them, and there were one or two cases of severe hardship. The T.U.C. leaders made statements that they were in Dublin in a purely "judicial" capacity. The older leaders hated Larkin, and hated militancy even more. The Daily Citizen openly sneered at him. Justice damned by faint praise, and only Lapworth's Daily Herald remained stoutly pro-Dublin. As the leaders of the British workers cajoled and bludgeoned them into treachery, representatives of the employers crossed to London seeking sustenance from their own class abroad. They obtained it without difficulty. They represented themselves as the defenders of business morality against the syndicalist Larkin who had torn up agreements and justified the sympathetic strike with the terse words "to hell with contracts". So ended the first phase of the struggle.

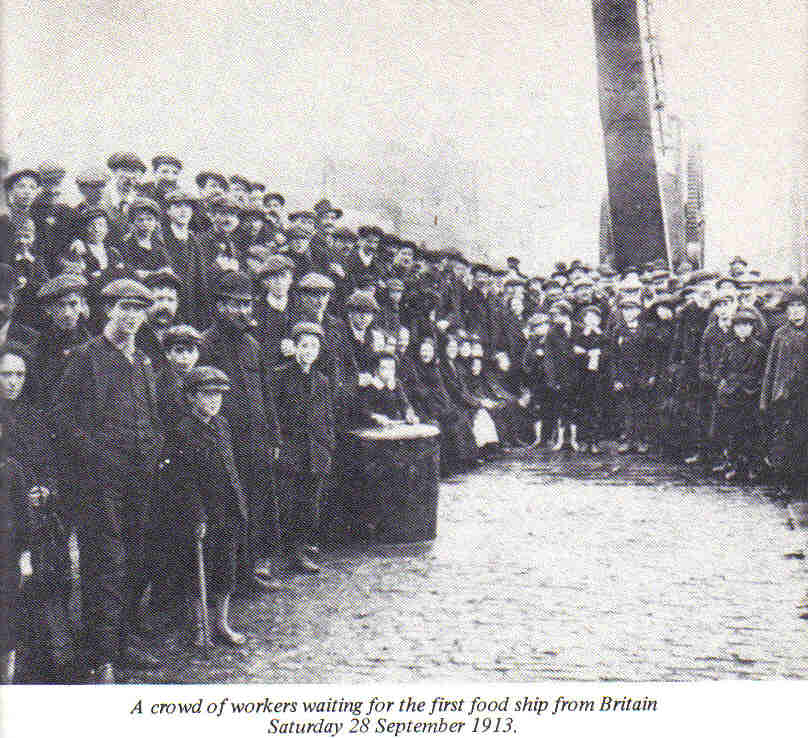

From condemning sympathetic strikes the British leaders turned to obstructing the "blacking" of goods in transit to Dublin. Here less sacrifice was involved and they had to face a rank-and-file vociferously demanding action. Unfortunately, they knew the weaknesses of their own people. For years it had been Britain's tradition to let others fight her battles while she supplied the weapons. Now the splendid solidarity movement was sidetracked into a campaign to send foodships to Dublin. As an adjunct to a sympathetic strike movement or boycott this would have been admirable. It was to be a substitute. In vain Larkin could reason or storm. The price of strike action was stated clearly on the ticket. It was London control of the I.T.W.U. Otherwise union funds were not to be risked on the Dublin intransigents. The right wing were endeavouring to confine British support to food and fuel, practical rather than political help, while making Larkin, who wanted the latter, seem ungrateful. Instead of the struggles of the two peoples being treated as one, the British were encouraged to think they were magnanimously sustaining the Irish in an essentially domestic affair, which to some extent they had involved themselves in foolishly. The leaders grudged. But the rank-and-file did not grudge. There was no mistaking the intense class feeling which brought pennies and sixpences from remote villages in Yorkshire and South Wales into the Dublin relief fund. But Larkin was right in his belief that sympathetic strike action alone could defeat the employers.

If it had been taken, the history of Western Europe might have been different. An issue of policy within the British labour movement thus contained the Dublin struggle like the banks of a stream and this explains Larkin's periodical outbursts against the right-wing leaders, as well as the tactics they adopted in Dublin. To Larkin they were guilty of industrial treachery. To Connolly there was also an explanation which lay deeper. It was to be found in the old Liberal-Labour alliance with the Home Rulers, which he had fought for twenty years. It was an aspect of the parliamentary opportunism of British Labour.

On his return to Dublin Connolly found a grimmer mood among the locked-out workers. When the Liverpool men returned to work the hopes of sympathetic action in Britain were finally dashed. A threatened split in the employers' camp had been healed by timely subventions from Britain. Connolly's return freed Larkin for lightning visits to Britain, where at packed meetings he urged without avail the resumption of the sympathetic strike. The leadership of the strike from now on slowly passed to Connolly. Starvation was on the way. Dublin suffragettes opened a soup-kitchen at Liberty Hall, where Countess Markiewicz supplied free dinners to the most needy. This service was augmented when the first foodship, the S.S. Hare, paid for by the British T.U.C. and loaded with £5,000 worth of C.W.S. food, arrived at the North Wall from Manchester on September 27. It was a fine gesture of solidarity and seemed to herald more active assistance to come. Enthusiasm was intense and Connolly was not the man to damp it. Yet he struck a reflective note within his speech of welcome. He compared the arrival of the ship to the breaking of the boom in Derry, the Unionist anniversary being now "put in the halfpenny place". But he went on:

"The chapter of Irish history dealing with the relief of Dublin by the labouring men of England will be a long and bright one. In order to obtain relief the trade union has surrendered nothing, not one particle of our independence. We have not been asked to surrender anything. We on our part are willing to accept the proposals of the Lord Mayor as a basis of negotiations. There may be some things in it that we may want to get out, but as a basis of negotiation it is an eminently reasonable proposal."

The essential condition insisted on by the union – withdrawal of the stipulation against union membership – had been accepted by the Mayor.

The employers on the other hand were dreaming of total victory through the use of blacklegs and were negotiating for a ship in which to quarter them in the safety of the Liffey.

"Moderate as I am," said Connolly, "I know what it means. If this ship is brought to Dublin by the Shipping Federation and they begin to discharge their cargo-I mention no names, as I want to give them a chance of withdrawing-I know, you know, and God knows, that the streets of Dublin will run red with the blood of the working classes."

Seddon attended a meeting of the Trades Council Executive under whose stamp the food was to be issued-i^. 8d. worth a head for sixty thousand persons. Supplies also came in from Aberdeen and Dumfries Co-operative Societies. The same day the employers rebuffed the Lord Mayor, and a Board of Trade Enquiry, presided over by Sir George Ask-with, the "licensed strike-breaker", was announced. Connolly thought it would "investigate what everybody knew", but when Gosling invited the Trades Council to nominate witnesses, he accepted delegation along with Larkin, O'Brien, Johnson, O'Carroll, D. R. Campbell, MacPartlin andRimmer. Robert Williams, the enthusiastic but unstable militant, attended for the Transport Federation, and despite the vituperative eloquence of T. M. Healy (the "most foul-mouthed man in Ireland") who enjoyed his brief for the employers, Murphy and his colleagues were publicly exposed as aggressors and protractors of the struggle. On October 7, George Russell (A. E.) wrote a celebrated letter to The Irish Times which described them as "blind Samsons pulling down the pillars of the Social Order", and told them: "You are sounding the death-knell of autocracy in industry ... so surely will democratic power wrest from you the control of industry.''

The statement of the workers' case was drawn up by Connolly.

"With due respect to this Court," he began, "it is neither first nor last in our thoughts today ... the ultimate tribunal to which we appeal is not this Court, but rather the verdict of the class to which we belong.... The learned Counsel for the employers says that for the past five years there have been more strikes than there have been since Dublin was a capital. Practically every responsible man in Dublin today admits that the social conditions of Dublin are a disgrace to civilisation. Have these two sets of facts no relation?"

He accused the employers of "enforcing their rights with a rod of iron and renouncing their duties with a front of brass".

"They tell us that they recognise Trade Unions. . . . They complain that the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union cannot be trusted to keep its agreements. The majority of shipping firms in Dublin today are at present working, refusing to join in this mad enterprise . . . with perfect confidence in the faith of the I.T.G.W.U. They complain of the sympathetic strike, but the members of the United Builders Labourers Union . . . have been subjected to a sympathetic lock-out."

The verdict was quite favourable. Askwith proposed a new basis for negotiations, involving reinstatement, withdrawal of the employer's pledge, and an arbitration agreement relinquishing the sympathetic strike for two years except when an employer rejected conciliation. "The strikers must not be victimised," declared Gosling. "On this point the masters will not yield," replied Healy. "Then," said Gosling, "we will fight."

A group of prominent citizens, anxious to succeed where officialdom had failed, seized upon these proposals to establish a "peace committee". Its delegates attended the Trades Council Executive. O'Brien pointed out that the workers had not rejected overtures. Connolly suggested an attempt to find an acceptable intermediary, the object being to bring the two sides together. But by early October both Protestant and Catholic Archbishops had declined that honour. The peace committee speedily learned that only the workers' side maintained a vestige of social responsibility.

The employers now clinched matters by declaring that no settlement was possible without the removal of Larkin and the appointment of new officials approved by the British joint Trade Board. Its experiences resulted in a complete change in the character of the peace committee.

Foodships were arriving at weekly intervals. The third arrived on October 13. The employers' demand for Larkin's removal (a subtle attempt to suborn Connolly) arrived when Larkin was beginning a tour which took him from Glasgow to Hull, Birmingham and London. He was taken ill at Nottingham and compelled to abandon his meeting in Aberdeen. Newspapers were not slow to point to the "responsible" alternative, but Connolly dashed their hopes by declaring "the position is unchanged" and organising a procession through the streets of Dublin on October 15. Four thousand marched with bands and banners.

At the meeting which concluded this demonstration, he announced that evictions had begun. "Pay no rent," Larkin had said. The advice was of course unnecessary. Families could not do so if they wished. One worker whose book was clear previous to the strike was served with an eviction order. He refused to move. R.I.C. men were sent to eject him, but being countrymen they declined. This was not the work they were called to Dublin to do. 'There was a limit to the brutality of the R.I.C.," said Connolly. But the Dublin police were not so squeamish. They broke in the door and smashed the remaining furniture, beating up both man and wife. The four children marched out defiantly singing "God save Larkin, said the Heroes". Such was the spirit of the working class.

The solidarity movement grew steadily and irresistibly. Both British and Irish suffrage movements rallied to the aid of the women and children. Committees were set up everywhere, encouraged by the Daily Herald and the Glasgow Forward, where Connolly wrote each week. The London Gaelic League forgot its pretended "non-political" character so far as to establish a special committee to raise funds for Dublin. The Trades Council was the general clearing house for raising and distributing funds, co-ordinating, and ironing out disputes and difficulties. Even in Belfast belated sympathy began to rise. The men, who had left the union in August, on account of the "ungodly speech" of their leader, applied to rejoin now. The employers at once gave them an unsolicited 2s. 6d. a week to keep them out. On the other hand workers of six or seven mills applied for membership of the union that was waging this titanic battle. Cathal O'Shannon, Nora and Ina Connolly took collecting boxes round church doors. The Gaelic League of Belfast came in. Finally Thomas Johnson was able to issue an appeal to the shipyard workers to forget sectarian differences and support their own class, and many of them responded. Such was the second phase - total deadlock.

In mid-October the cause suffered a set-back. Up to then the obvious reasonableness of the workers contrasted with the employers' intransigence had carried all before it. In October secondary effects of the strike began to appear. Small businessmen closed down through lack of materials. Established Corporation employees, laid off for the same reason, were told that they had lost their seniority. Shopkeepers and small landlords began to feel the pinch. These classes read Arthur Griffith's Sinn Vein, the only paper (apart from the yellow sheets of the A.O.H.) which saw no harm in the employers. Griffith saw in the foodships, not solidarity taking the only course left open to it, but a nefarious plot to advance British exports over the ruins of Irish trade. He thundered against "Marx's iron law of wages" and the "neo-feudalism of Marx, Proudhon and Lassalle". An ignoramus in all theoretical and scientific matters, he was unaware that his own suspicion of Trade Unionism was shared by Proudhon whom Marx had immortalised by destroying his reputation. When the pent forces of solidarity broke through at a fresh point, the backward strata were quick to misinterpret and condemn. The precondition for what took place was, however, the refusal of the British trade union leaders to take sympathetic action.

A group of suffragettes connected with the Daily Herald League in London proposed a plan for bringing the children of the strikers to be cared for in the homes of British workers. A similar scheme had been adopted in the New England Textile strike and it is surprising that Mrs. Montefiore, who was widely travelled, did not fear a repetition of the sectarian repercussions which wrecked it in America. The Parliamentary Committee of the British T.U.C. gave no countenance and insisted that its own funds must be devoted to supporting children in their own homes. But the T.U.C. was suspect owing to its obstruction of sympathetic action, and was unfortunately in this instance not heeded. An announcement brought many applications from parents anxious to spare their children the miseries of Dublin. Foster-parents were found in London, Edinburgh, Plymouth and above all in Liverpool. Later the scheme was extended to the outskirts of Dublin and to Belfast, as it caught the imagination of sympathisers.

Larkin seems to have given tacit approval. Connolly was extremely dubious but, presented with a fait accompli, left Dublin to fulfil engagements in Edinburgh and Dundee. He spoke at Leith, where students tried to break up the meeting, and from the bandstand in the centre of the Meadows, his old stamping ground. At Dundee his brother John had the temerity to appear at the platform in the uniform of the Edinburgh City Artillery, and was denounced in fine style. He went on to Glasgow and Kilmarnock, to reach Dublin once more on October 28. He found Larkin in jail, under a seven months' sentence, and outside a seething pot of Hibernian provocation. The suffragettes had gone quietly about their business while Larkin was occupied with his defence. A true bill was found on the twenty-first, and Larkin was convicted on the twenty-seventh as fifteen thousand men, women and children cheered encouragement from outside the court. The jury was composed of his opponents the employers, and one, with more compunction than the rest, who declared his interest, was refused exemption. "A packed jury," Larkin commented. He was within an ace of victory in his English campaign. So deftly had he laid about him that Labour leaders had asked the strike committee to "restrain him". "Larkin must go" became the right-wing cry, because "he stands in the way of a settlement". But after his speech at the Picton Hall, the Liverpool dockers declared themselves ready to strike once more. The employers and Hibernians had therefore good reason to try to discredit him during his trial and prepare the way for the importation of scabs. They found their opportunity in the campaign against the "deportation" of the children.

Four days after the first children left on the seventeenth, the Archbishop of Dublin broke his judicial silence. He denounced the "deportation" as a danger to the children's faith. The Hibernian rags then published a membership certificate of the Orange Order in the not uncommon name of James Larkin, and accused the strike leader of proselytising. Some children reached Mrs. Griddle and Fred Bower in Liverpool, others the Pethwick-Lawrence family in Surrey. Then the riots began. With fanatical young priests at their head, howling mobs surrounded the quays and stations. Both parents and children were injured in their attacks. Despite the declared fact that the only Protestant accommodation in Belfast was that offered by D. R. Campbell, Amiens Street was the scene of wild hysteria. Mrs. Montefiore and her colleagues were arrested. Palpable evidence that religious facilities were fully available was ignored or brushed aside. Under this smokescreen "free labour" was brought over from Manchester. When Connolly found himself acting general secretary of the union it seemed only one more tribulation was necessary. Seddon and Gosling announced their intention of paying another visit with a view to "settling" the strike.

Connolly's handling of this complex and unfavourable situation was masterly. His strength was the tremendous momentum the mass movement had by now attained. Within three weeks he had turned the tables on all his adversaries, and got Larkin out of jail. The first step was to inform the press that in view of the opposition the transmigration scheme had been abandoned. Instead, he demanded that the children be supported in Dublin. He then suspended all free dinners at Liberty Hall. "Go to the Archbishop and the priests," he told his supporters. "They are loud in their professions. Put them to the test." They failed to pass. Catholic relief and charitable organisations were so overwhelmed with demands that Archbishop Walsh was compelled to adopt a conciliatory tone. Now at last he issued an appeal for the settlement of the dispute.

Dinners were resumed after a week. To workers who had been carried away by the hysteria, Connolly was indulgent and helpful. His old neighbour, Mrs. Farrell, had been arrested during a riot in which Sheehy-Skeffington was injured. He visited her in jail, bailed her out and offered to arrange defence counsel. By this means he drew back into the struggle workers who had strayed.

He rallied the locked-out men in Beresford Place. To his question "Will we give in?" husky voices cried, "No surrender!" The imprisonment of Larkin had an effect opposite to that which was intended. It was hoped that Connolly would seize the opportunity to oust Larkin and become leader himself. He was in his own testimony "subjected to influences that none could imagine", particularly from across the channel. But instead, his skill and firmness saved the situation. "Messrs. Seddon and Gosling are coming over again to negotiate," he told the Daily Herald, "and we heartily accept the co-operation of our comrades across the water as our allies. The moment they are anything less than that we arc ready to dispense with their co-operation. If we are to judge by the capitalist press, some of our English comrades are susceptible to the blarney of soft-spoken Dublin employers, but we are giving them the credit of not being easily wheedled out of their allegiance to the working class."

To the Dublinmen he was even more outspoken. "If the trade union leaders from across the water are prepared to accept peace at any price, and threaten to withdraw their foodships and support... then I would say 'Take back your foodships, for the workers of Dublin will not surrender their position for all the ships on the sea'." Seddon and Gosling arrived. The Trades Council Executive rejected their proposal for a settlement without the I.T.G.W.U. Connolly's refusal to disavow Larkin left no-room for manoeuvre.

Securing Larkin's release was the next problem. His imprisonment was widely held to be illegal. He was acquitted on all counts save that of sedition. But among his seditious utterances the worst that could be listed were such dynamite-laden statements as that he denied the divine right of kings, opposed the Empire and that "the employing class lived on rent and profit". The sentence, said Connolly, showed the class character of the administration of the law. At a protest meeting he announced his plan to defeat the Liberal candidate in each of three by-elections which were pending.

"It doesn't matter," Connolly declared, "whether it is a Labour man or a Tory that is against the Liberal. The immediate thing is to hit the government that keeps Larkin in jail." If these measures were without effect, bolder ones would be taken.

A manifesto was wired to Keighley, Reading and Linlith-gow. "Locked-out Nationalist workers of Dublin appeal to British workers to vote against Liberal jailers of Larkin and murderers of Byrne and Nolan." Belfast Branch of the I.L.P.(L) followed with a telegram to Keighley, where Dev-lin was busy helping the Liberal. On the exposure of the strike-breaking activities of his A.O.H. (Board of Erin), that gentleman hastily cancelled his meetings and slunk out of the town.

Partridge was despatched to Reading where he joined Lansbury in support of the Labour candidate. At the funeral of James Byrne, secretary of the Dun Laoghaire Trades Council, who had died on hunger strike, Connolly declared: "The government must go if Larkin stays in." The occasion became a great anti-government demonstration which filled the Home Rulers with a deep uneasiness. Every shop in the town closed while the procession passed.

"My heart swelled with pride," said Connolly, "that the workers are at last learning to honour their fighters and martyrs. Byrne as truly died a martyr as any man who ever died for Ireland." He remarked that the employers had at last been forced into a semblance of negotiation. They would now try to protract discussions while they brought in fresh scabs.

The news of the government defeats in Linlithgow and Reading caused great jubilation in Dublin. Sky-rockets were fired from the roof of Liberty Hall. "We are doubtless to be told we are attacking Home Rule," said Connolly. "Dublin working men are as firm as ever for national self-government. But they are not going to allow the government to bludgeon them and jail their leaders and comrades and place all the machinery of the law, police, and military at the disposal of the employers without hitting back. Reading is the first blow. Follow it at Keighley, and at every election till Larkin is free."

On November 12 the Liberals were defeated at Keighley also. The prestige of the Home Rulers fell disastrously. The Dublin working class now understood the meaning of Home Rule under the Hibernians. Two months of struggle taught them the truth of Connolly's twenty years' propaganda.

Lost by-elections did not suffice to move the government. Nor did the rapidly mounting release campaign in Britain, which was now joined by the Liberal newspapers, the News and Chronicle. Scabs poured in, fifty from Manchester on the 29th, and one hundred from Liverpool on November 5. The Daily Herald called for a general strike, Robert Williams for a special conference of the T.U.C. Connolly did not wait. Throughout Dublin he posted his own manifesto. Everywhere groups of men were to be seen reading and discussing it. It was headed 'Importation or Deportation?" and flayed the hypocrisy of those who "prostituted the name of religion" by pouring "insults and calumny upon the Labour men and women who offered the children shelter and comfort... but allow English blacklegs to enter Dublin without a protest."

The manifesto then announced that "individual picketing" was abolished. Mass picketing was to be the rule, and those who shirked were to be refused food tickets. It concluded:

"Fellow workers, the employers are determined to starve you into submission, and if you resist to club you, jail you, and kill you. We defy them. If they think they can carry on their industries without you, we will, in the words of the Ulster Orangemen, take steps to prevent it. Be men now, or be for ever slaves. – James Connolly."

The authorities replied by arming the scabs. One of them, driving a load of cement, drew a revolver and shot a boy in the knee. He was not arrested, but his load of cement was soon strewn about the road.

It was the struggle of the workers against the police-protected armed scabs which gave rise to the Citizen Army. Its origin has been disputed but seems clearly ascertained. When the first rumours of the introduction of scabs were noted, the Daily Herald issued the slogan "Arm the Workers". But it was not giving voice to any new conception, certainly not in syndicalist propaganda. Larkin attributed the notion of a citizen army to Fearon of Cork in 1908. But in the U.S.A. it would have been unthinkable not to arm pickets where this was possible. The Workers' Police of Wexford has already been referred to.

On October 31 a correspondent in the Daily Herald had urged the T.U.C. to create a "Civil Guard" to protect civil rights. At Dun Laoghaire Connolly also had referred to the need to arm the workers. Talk of workers' defence was in the air; it arose from the inescapable needs of the situation, and required but a catalyst to set it in action.

On November 11 the Industrial Peace Committee dissolved. A majority decided to abandon the position of impartiality and give full support to the workers' side. The events which precipitated this decision were the use of three companies of Surrey infantry to protect Jacobs' scabs and the government decision to increase the pay of the police who were trying to disperse the massed pickets. A new committee was formed, under the chairmanship of Captain Jack White who had resigned his commission on account of his anti-imperialist views. The inaugural meeting of the "Civic Committee", as the majority called itself, was held on the twelfth at 40, Trinity College, and one of the proposals made by the Captain was a "drilling scheme" as a means of bringing "discipline into the distracted ranks of Labour". It is of course hard to believe that Captain White did not envisage the possible consequences of such a course. He approached Connolly, who had just played his trump card for the defeat of the scabs and the release of Larkin.

This was the Manifesto to the British Working Class, calling on them to stop all traffic from Messrs. Guinness, Jacobs and other scab firms. Connolly had thus resumed the struggle for sympathetic action, and appealed over the heads of the right-wing leaders.

"We are denied every right guaranteed by law," he declared, "we are subjected to cold-blooded systematic arrests and ferocious prison sentences. Girls and women are jailed every day. 'Free' labourers are imported by hundreds.

"We propose to carry the war into every section of the enemy's camp. Will you second us? We are about to take action the news of which will probably have reached you before this is in your hands."

That news aroused even the "respectable" classes to grudging enthusiasm, and on the mass of the workers its effect was electrical. Connolly had closed the port of Dublin "as tight as a drum". All over England "vigilance committees" were elected. Meetings of railwaymen decided not to handle tainted goods in Liverpool, Birmingham, Holyhead, Swansea, Bristol, Heysham, Manchester, London, Nottingham, Crewe, Derby, Sheffield, Leeds and Newcastle. This action opened the fourth phase of the struggle.

In vain 'the Dublin shipping companies pleaded their agreements. This was no ordinary dispute, Connolly told them. The result was almost magical. Larkin was released at 7.30 a.m. on the thirteenth. The two men then drafted a further appeal to the British workers calling for a general strike to stop the transit of scabs. That Thursday night there was a great victory meeting and procession, the biggest yet held. Until after midnight boys and girls lit bonfires in the streets. Larkin did not speak, however. He was suffering from a nervous reaction. Frothing and fuming in his cell he had not been able to orient himself to Connolly's strategy. Men of feeling tend to think mechanically. Why had Connolly accused Murphy of refusing agreements and then torn them up himself? Larkin's frustration could only be purged in action. He left for Liverpool on the Friday, thence to carry his "fiery cross" throughout England. It was Connolly who startled the victory meeting with these words:

"I am going to talk sedition. The next time we are out for a march I want to be accompanied by four battalions of trained men with their corporals and sergeants. Why should we not drill and train men as they are doing in Ulster?"

He asked every man willing to join the "Labour Army" to give in his name when he drew his strike pay at the end of the week. He had competent officers ready to instruct and lead them, and could get arms any time they wanted them. The announcement was greeted with deafening cheers.

Connolly remained acting general secretary and editor of the Irish Worker, but left McKeown in temporary charge while he joined Larkin in Manchester where four thousand assembled in the Free Trade Hall with another twenty thousand outside. "The working class of Dublin is being slowly murdered," Connolly told them.

In this fourth stage of the struggle, practically the entire working class of Dublin was engaged. The bulk of the intelligentsia had joined them. Republicans like Pearse and Clarke looked on with admiration at such a stupendous resistance, and slowly a new comprehension dawned. Both sides were receiving thousands of pounds a week from Britain. But it was a condition of working-class victory that the employers should be prevented from producing or distributing. The steady trickle of scabs enabled the more fortunate businesses to tick over, and though not a ship left Dublin, Derry and Belfast were still open. For this reason the fight against scab labour in Dublin was little more than a holding operation until there was sympathetic action above all in Liverpool and Glasgow.

Connolly accompanied Larkin to London where they met the Parliamentary Committee of the T.U.C. on the Tuesday, urging either a general strike or a total boycott of Dublin. There was no response. Nor was there immediate consent to Williams' proposal for a special meeting of the T.U.C. Next day the two colleagues spoke at the famous Albert Hall meeting, when students risked burning the place down in an attempt to plunge the auditorium into darkness. Fortunately they were too ignorant of electricity to achieve either. Instead they swarmed over the balconies, interrupting the quieter speakers, creating pandemonium until they were ejected by a group of burly stewards led by Con O'Lyhane. Once more Connolly and Larkin stressed the need for sympathetic action and demanded a special T.U.C. meeting. They were joined by George Lansbury, Will Dyson, Robert Williams, George Russell, George Bernard Shaw and Sylvia Pankhurst.

Connolly made a flying visit to Belfast, where he addressed a meeting at the low docks. The local men had been called out because the Head Line had transported scabs to Dublin. There was to be no return till the Dublin men won. The example of Dublin was increasingly impressing the Protestant workers, and it is noteworthy that when a meeting at King Street a thousand strong celebrated Larkin's release, "Dolly's Brae" was silent, and a mob of Hibernians tried to break it up. Noteworthy also was the fact that the police arrested not the Hibernians but the trade unionists.

Reaching Dublin the same night Connolly attended the first public meeting of the "Civic League". Captain White had advised Trinity College students to absent themselves from lectures as a protest against. police protection of the scabs. The authorities replied by announcing that any student who attended "Captain White's Home Rule meeting" would be deprived of his rooms. The Mansion House being refused to them, the Civic League hired the Antient Concert Rooms and Connolly was delighted to see over a hundred college boys arrive in a procession. They were allotted seats on the platform. Among the speakers were Rev. R.M. Gwynn and Professor Collingwood of the National University, Countess Markiewicz, Sheehy-Skeffington and Darrell Figgis. A telegram from Roger Casement supported the "drilling scheme" as a step towards the foundation of a corps of national volunteers. Connolly had referred to the proposed force in his Albert Hall speech as "a citizen army of locked-out men" and the name "Citizen Army" seems to have been adopted immediately after Captain White's meeting. It was first used officially on Sunday November 23, when after a further recruiting meeting two companies were formed. It was thus at first essentially a labour defence force, though Connolly's speeches and Casement's telegram show that there were inklings of its ultimate destiny. Captain Monteith was on his way to join when he met Tom Clarke, who dissuaded him on the grounds that his help was required in the purely nationalist "Volunteer" movement then being prepared.

The Citizen Army drilled with hurley-sticks and wooden shafts at Croydon Park. For practical purposes the shafts were sometimes "shoed" with a cylinder of metal. A favourable reaction was immediately noticeable among the police. Scabs still came in. Devlin still screamed for the establishment of a "Catholic Labour Union". But he merely isolated himself. The working class had already won its moral victory. When the annual Manchester Martyrs procession took place, the I.T.G.W.U. dominated it with the largest contingent of all. The A.O.H. deemed it prudent not to appear. The working class had dislodged them from the body of the nationalist movement. In the same week the British T.U.C. conceded Larkin's request and announced a special meeting on December 9.

The two weeks preceding this conference were crucial. Larkin travelled from city to city arousing intense excitement. At Birmingham and Liverpool, Connolly joined him. No day was without at least one meeting. Cardiff, Swansea, East Ham, Hull, Leicester, Edinburgh, Newcastle, Leeds, Preston, Glasgow, and Stockport were covered before the conference, and Larkin made one brief appearance in Dublin. The right-wing leaders also mobilised their forces. Fearing the opinions of their members, they called not a delegate conference but a conference of paid officials. J. H. Thomas gave orders that on the first occasion the Transport Union unloaded a ship, all his men must return forthwith. Havelock Wilson denounced sympathetic strikes and encouraged his members to work the Head Line ships. The Daily Citizen attacked Larkin bitterly and incessantly. Larkin, unfortunately, saw these attacks not as signs of a political trend but as acts of personal apostasy. He replied in kind and with interest. Liverpool carters and motormen struck work. When two Llanelly railwayman were dismissed for refusing to handle goods for Dublin, the resultant strike spread throughout South Wales. Funds were now arriving from Australia and America, and news arrived that the French workers were preparing to close the ports against all goods originating in Dublin.

Protected by the staves of the Citizen Army, Connolly now led processions past Mountjoy to sing rebel songs for Frank Moss, who was on hunger strike. He skilfully outwitted the police so as to pass singing by the Convent where Mary Murphy was imprisoned. As many as twelve thousand gathered in Beresford Place. The remaining support for the employers ebbed steadily. When the Irish Volunteers were founded on November 25 at the Rotunda, Lawrence Kettle, whose family employed scabs on Co. Dublin farms, was hooted off the platform amidst pandemonium. Pembroke Urban Council decided to apply penalty clauses against builders who had ceased work on its housing scheme. Archbishop Walsh appealed once more for peace and, most significant of all, the Freeman's Journal crossed over to the position of The Irish Times, urged the employers to give up their ban on the Transport Union, and left the Independent alone on the employers' side. Sharp divisions appeared in the Dublin Chamber of Commerce, where Murphy's dictatorial behaviour was becoming more and more resented.

England was decisive. Boycott Dublin goods for two weeks, and the employers would have to cave in. Larkin saw the Parliamentary Committee once more. Instead of blacking Dublin goods, they elected one more delegation, the "strongest yet", which visited Dublin determined to effect a settlement at all costs, if need be over the heads of the local committees. The employers could scarcely decline to talk. The 'Daily Mail was clamouring that "Larkin and Murphy must both go" and Murphy knew his position was now none too strong. Connolly and Foran represented the union, O'Brien and MacPartlin the trades council. Arthur Henderson tried desperately to jockey the Irishmen into an unacceptable settlement. The employers sat in one room, the workers' representatives in another, and the British passed back and forth between them. Only for fifteen minutes did both sides sit together. Experienced diplomats they might be, but the Englishmen could find no half-way house between Gabriel and Beelzebub. The conference broke down after an allnight sitting, on the question of reinstatement - two days before the special T.U.C. in the Memorial Hall, Farringdon Road.

Before leaving for London, Connolly posted up another manifesto in which he laid the blame for the breakdown squarely on the employers. The conference was on December 9, and ostensibly there were two alternative policies presented to it for a choice. The right-wing proposed a 1d. levy to send Dublin £12,500 instead of the present £5,000. The left-wing demand was for a boycott of Dublin goods and, if necessary, a national strike to prevent victimisation.

On the eve of the conference J. H. Thomas settled the South Wales strike on terms of "abject betrayal". The attacks on Larkin intensified. Larkin himself grew more openly contemptuous of the "milk and water" cross-channel leaders. His emotional outbursts probably did far less harm than his occasional mechanical attempts to think his way out of a difficulty. He was billed to speak at Grimsby, but declined on the ground that the proposed chairman, Ernest Marklew, had divorced his wife. Most probably his motive was to avoid any other possible clash with the Catholic Church on a moral question. But the refusal created a very bad impression in Britain while it was scarcely noticed in Ireland. Blatchford's Clarion published a blistering "Open Letter" to him. Sick with a sense of defeat and betrayal he laid about him even more determinedly. Clarion described him as a "devoted Catholic". While the B.S.P. was the backbone of the solidarity movement, Justice had remained serenely detached. It now suggested that Larkinism was a Catholic plot to discredit the trade union leaders, with the complicity of the Daily Herald. Yet at the Sun Hall, Liverpool, Larkin had described Father Hopkins as "masquerading in a cassock and gold cross" adding: "We want none of these sky-pilots; we can pilot ourselves."

Six hundred delegates attended the conference, representing three hundred and fifty unions. But a glance convinced Larkin that he was on trial, and before a jury of his enemies. Robert Williams and he both complained the delegates had been neither elected nor mandated. Williams himself was excluded, on the grounds that as secretary of the Transport Federation he was paid by nineteen unions and was therefore not eligible.

At the outset it became clear that far from being called to assist Dublin, the conference was assembled to betray it. The first item on the agenda was the resolution accepting the report of the deputation to Dublin. It was moved by Hen-derson, who dropped his bait in the form of veiled insults directed at Larkin. Gosling, on the other hand, gave a fair account which laid the blame for the position on William Martin Murphy. Connolly smoothed things over by assuring Henderson that he need fear no opposition from Dublin should the T.U.C. feel disposed to open up fresh negotiations at any time.

Ben Tillet then moved a resolution condemning "unfair attacks" on trade union leaders. J. H. Thomas accused Larkin of sowing dissensions in the ranks of British railwaymen. Havelock Wilson said there was "Murphyism" in the trade union movement as well as among employers. Larkin, overworked and exhausted, taunted and exasperated beyond endurance, gave himself the pleasure of speaking his mind clearly for fifteen minutes.

"Mr. Chairman, and human beings," he began, and in a speech which was continuously interrupted he spoke of the "foul, lying attacks" made against him. "Not a man in this hall has been elected," he thundered, and demanded the blacking of Dublin goods. The resolution was carried on a card vote with a big majority.

Then came the resolutions to call conferences, continue consultations, use every legitimate means, and so on. Generosity was not unending, it was hinted. The situation should be an object lesson to those who tried to create dissension. The gas-workers' delegate, Jack Jones, had the clarity of vision to suggest fighting capitalism not Larkinism, and proposed the boycott. Davis of the Vehicle Builders seconded. Railwayman Williams described the proposition as "silly". Robert Smillie objected that the rank-and-file had given no mandate for a national stoppage. Delegates supporting Larkin were constantly heckled, and the Jones amendment was lost by two million to two hundred thousand. One of the meaningless resolutions was then carried.

Larkin was speechless with indignation. Lacking theoretical understanding of the mainspring of the treachery before him, he was stupefied like many an honest man who sees duplicity his own mind cannot encompass. He had been hopelessly outmanoeuvred on a stage which had been cunningly set. It was Connolly who found words, and he spoke moderately.

"I and my colleagues from Dublin," he said, "are here under a deep sense of humiliation. It would have been better for the conference to have first endeavoured to try and settle the Dublin dispute and afterwards wash their dirty linen. The reverse has however been the case." He thanked them for the help they had given but warned them: "We in Dublin will not necessarily accept all the resolutions passed at this conference."

Larkin left for Glasgow. Connolly returned to Dublin. On the way he leant out of the carriage window at Crewe and bought a newspaper. To his surprise it announced the resumption of work at the North Wall. Thomas had already ordered his men back to work before the conference met. If they did not return they would get no strike pay.

In Dublin there was no weakening, and Connolly confined himself to a simple statement of what had passed. But the final stage of the struggle had now opened. The foolish obduracy of Murphy precluded a settlement. But neither side was in any position to fight on. There could only be a disengagement. The remarkable fact is that this disengagement took as many months as were required to reach the crucial deadlock. Peace talks were begun again, and dragged out with intermissions. No settlement was ever come to between the main contestants, but step by step their allies resumed the status quo, or something near it. The London conference, which wrecked all hope of a workers' victory, released the smaller employers from their dependence on Murphy. The Irish Times demanded the unconditional reinstatement of all locked-out men-a category which included all but those tram-waymen who had struck in protest against the dismissal of the parcels men.

In mid-December this outcome could not be clearly foreseen. Connolly resumed his meetings, devoting much attention to the municipal elections, which he hoped to make a dazzling demonstration against the employers and government. The armed scabs grew more arrogant as their numbers increased. An old woman was shot, without any arrest being made. But when the same treatment was offered the Vice-Chairman of the Docks Board it was a different matter. The scab without respect for the gentry, when arrested, was bailed out by his employer. The Citizen Army continued to drill and defend the pickets, but shortage of arms drove many to transfer to the Volunteers.

When it was clear that Devlin's attempts to start a sectarian breakaway were doomed to failure, A.O.H. hoodlums broke into the Irish Worker printing office, smashed the formes and scattered the type. Police arrived. They prevented further damage but refused to make any arrests. A few days previously Hibernians had broken up a meeting of the Irish Volunteers in Cork city.

Less than a week after the London conference, British leaders dealt fresh blows at Dublin. The Seamen's and Firemen's Union ordered its members to man the boats of the Head Line though they were being discharged by Shipping Federation scabs. In both Dublin and Belfast the members refused. They were then informed that union men would be brought from England to fill their places. A consignment of Guinness refused in Dublin was despatched to Sligo. Connolly wired his local branch. Blacked in Sligo, it was taken by rail to Derry, where N.U.D.L. dockers loaded it, N.S.F.U. men took it to Liverpool and Sexton's dockers discharged it.

Connolly called a meeting of his Executive Committee. There was obviously now no point in keeping up the port-workers' strike. Foodships had ceased and contributions were rapidly falling. The T.U.C. had done nothing but promise another mediation team. It was decided to permit dockers to return to work "without prejudice to negotiations or a subsequent settlement". The smaller firms accepted them willingly, and they went back "with the Red Hand up".

On the day of the E.C., Larkin returned. He held an impromptu meeting at Dun Laoghaire and reached Dublin just in time to be evicted from his house. He had paid no rent since August 18. But he was full of fight. "The struggle is not half over," he declared. His spiritual stature was shown in those days of destitution and betrayal. He knew the E.C. decision was inevitable, but may have discharged his nervous tension through some words upon it. Newspapers reported a quarrel between Larkin and Connolly, to which they attributed Connolly's return to Belfast before Christmas.

This was the Christmas of hunger and heroism. "Dublin lies in the grip of the power of the purse," Connolly wrote. Every effort at mitigation was made by the union's faithful auxiliary workers. A huge marquee was erected at Croydon Park, and twenty thousand children were given a square meal. The O'Mahony provided Wicklow venison for one thousand men. Most of the prisoners in Mountjoy were released for Christmas, but not from good will. The warders threatened to strike themselves if their duties were not lightened over the holiday.

Connolly spent Christmas expanding The Reconquest of Ireland for pamphlet publication. On his return, Larkin and he issued a joint manifesto; it was made clear that Larkin had made a rough sketch, Connolly had drafted it, and both had signed it. So much was required to silence the tongue-wagging of those who were aiming for a split. The manifesto affirmed their intention of continuing the struggle and called for increased aid from both Ireland and Britain.

On January 4, 1914, they spoke together at the funeral of Alice Brady, a sixteen year old girl who died after being shot by a scab. Her assailant, then on bail, was taken in a second time and charged with murder. He was acquitted on the Judge's direction. Connolly seems to have caught a chill at the funeral. He returned to Belfast to lecture to the I.L.P.(I) branch on the tenth and remained there a fortnight while his wife nursed him through his only recorded illness. He was not well enough to attend the Belfast office until January 20 and could not accompany Larkin to London to seek clarification of the position of the T.U.C. Larkin and O'Brien came back with the news that all aid to Dublin had now ceased. The fund was formally wound up on February 10, the thousands who had been on strike for nearly six months being handed over callously to their starvation. It is significant that two days later Asquith announced his first scheme for the partition of Ireland.

Taking Connolly's place in forward during his sickness, Larkin explained that despite a number of settlements there were still nine thousand strikers. The election results showed the mood of the people. There were 12,026 pro-Larkin votes against 14,978 for the nationalists. Labour was within an ace of a majority, and the Archbishop congratulated the Mayor on his narrow escape. But Dublin was isolated and Dublin was starving. Visitors described the terrible plight of the people, women dressed in shawls and skirts, in mid-February devoid of a stitch of underclothing, children ten years old dressed entirely in sacking. Reactionaries took heart. Father Kane resumed his attacks on socialism. The A.O.H. started to develop a new tactic of infiltrating into trade unions and secured a complete capitulation by the United Labourers, which destroyed the union. Martin Murphy demanded that the government deport Larkin to England. At Liberty Hall, meetings were held at which lists of firms who still operated the employers' pledge were drawn up. The workers of all others were advised to return. By this means the burden on the union was gradually diminished.

As soon as Connolly was fit, the two leaders went to Glasgow, where they appealed to the "advanced section in Britain" not to desert Dublin. For the remaining two months of the struggle the B.S.P. carried the main burden of organising relief. British Labour indeed paid its own price for December 9. The middle-class backers of the Daily Herald forced Lansbury to dismiss Lapworth. "Too much Dublin" was the complaint. At the end of December London master-builders locked out their own workers. The Herald, under its new management, was reduced to eight pages. The great unrest quieted; once more British democracy suffered defeat because it failed to extend its full solidarity to the people of an oppressed nation. Only one union, the A.S.E. [Parent body of the Amalgamated Engineering Union] voted a 3d. levy in response to Larkin's new appeal. In the months that followed the British people were being led by their leaders ever nearer the slaughter of the first world war.

Connolly now returned to Belfast, while Larkin continued to raise funds in Britain to cover the retreat of his army. Aid now took on another form. The socialists organised meetings and concerts for Dublin. Delia Larkin took a troupe of players through Lancashire. The Lord Mayor of Liverpool was prevailed on to patronise a distress fund in that City. Connolly's weekly articles in Forward returned to the subject of Dublin again and again. No experience had moved him so much in his life. He must dwell on it all the time. His old friends of the S.L.P. in Glasgow, from whom he had been estranged since the final breach with De Leon, began to rally round him again. But the socialist advance-guard, however welcome, was a poor substitute for the main army of labour.

A thousand I.T.G.W.U. men in Belfast were still locked out, and no arguments would persuade the Head Line to employ them. Connolly visited Glasgow and London in an effort to get the Stevedores Union to boycott the company. By mid-March, however, it was clear that the employers refused to distinguish between the I.T.G.W.U. and the S.F.U. men. Negotiations were opened between the two unions with a view to joint action. Adversity had forced them to compact. The same week, Jacobs' girls returned to work.

Lenten pastorals denouncing socialism and syndicalism had no influence on the starving workers. Connolly challenged the Hierarchy to name one point the union had refused to concede which the Archbishop himself, placed in the same position, would have conceded. Men now signed the Murphy pledge, but many remained members of the union. They continued to pay their subscriptions at Liberty Hall. There were no sackings. The pledge for which the capitalists had starved, murdered and tortured men for eight months was now reduced to a scrap of paper whose provisions they could not enforce. They could humiliate their returning employees, scoff at their emaciation and raggedness. Yet the battle was drawn. The employers had gained nothing they set out to gain. Their weaker members were bankrupt, and they dare not repeat the challenge to labour. It was too strong. But the Irish national struggle had been dealt a deadly blow.

In his weekly articles Connolly showed deep insight into the dynamics of the struggle, its importance for the British working class, and its connection with the Home Rule question. In Old Wine in New Bottles he tried to answer theoretically the question why the British unions had failed to respond to the call of class solidarity. He naturally avoided the vulgar nationalist pitfall of blaming them because they were British, though it is doubtful if he ever again felt any sense of confidence in the British labour movement. He did not, like Lenin, link up opportunism in the labour movement with the growth of imperialism. This was not yet clear. Rather he looked back to the early I.W.W., "the first Labour organisation to organise with the definite ideal of taking over and holding the economic machinery of society". He explained the syndicalist ideal of industrial unions linked into "one great union" where one membership card covered the "whole working-class organisation".

Then he raised questions which led beyond the syndicalist horizon. He had observed the process of amalgamation and affiliation which had produced, for example, the Transport Workers' Federation. The enlargement of organisation had been accompanied by "a freezing up of the fraternal spirit". The sudden strike, which had "won more for Labour than all the great labour conflicts in history", was replaced by the war of massed battalions "on a field every inch of which had been explored and mapped out beforehand". The amalgamations and federations had been, without exception "used in the old spirit of the worst type of sectionalism".

"Fighting spirit is of more importance than the creation of the theoretically perfect organisation," Connolly concluded. But how was it to be maintained? "The only solution of that problem is the choice of officers, local and national, from the standpoint of their responsiveness to the call for solidarity." Here he stopped short. Who was to look after the keepers? The De Leonist duology had become a trilogy: trade unions for "direct action", a Labour party for organising votes, and a socialist party for propaganda. But the socialist party was relegated to third place. Connolly needed and was feeling for the missing link, the socialist party of a new type which would provide the working-class movement with its incorruptible cadre. Without it he could only advise in general: "Choose the right man." The tragedy of his untimely death two years later is that his political advance was cut short. Nobody in Ireland developed these questions further, and underestimation of the role of the party has dogged the Irish labour movement for forty and more years.